Getting a job working in Antarctica is undoubtedly a unique experience very few people can brag about.

For Supply Tech Jim Huston of Iowa, he’s part of an even more exclusive group of individuals that miraculously survived a heart attack while “on the ice” (in Antarctica).

Now, he’s sharing about life in Antarctica’s largest research facility, McMurdo Station— and what an emergency medical evacuation at the end of the world is really like.

[joli-toc]

Antarctic Program Background

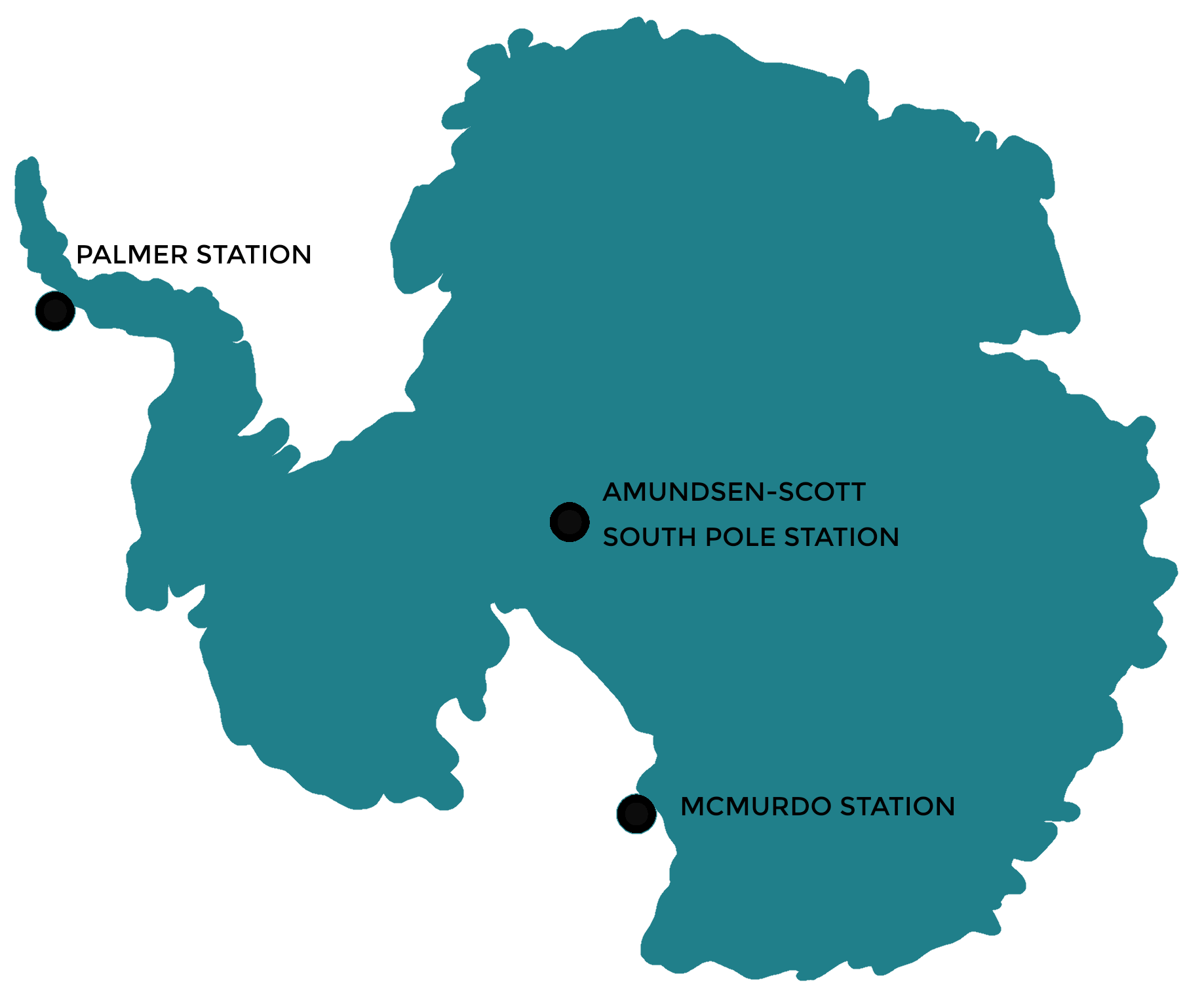

Since 1959, the United States Antarctic Program (USAP) has sent thousands of scientists and contractors to its three Antarctic research facilities: Palmer Station, Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, and McMurdo Station.

During the primary summer season from October through February, researchers from a range of disciplines work out of the stations as well as remote field camps to study everything from glaciology to astrophysics.

Non-scientific personnel, or support staff, work year round to ensure that the polar facilities and infrastructure run smoothly. These individuals include cooks, janitors, mechanics, electricians, and many more.

Meeting Jim

I first met Jim while staying in the same hotel in Christchurch awaiting our flight to McMurdo.

Along with another friend, we quickly became each others’ “ice family.”

Antarctica brings together people of all backgrounds, and sometimes the jobs you have at home are completely different from the ones you hold on the ice.

While I was a steward (dining attendant) on station, I’d previously been an ESL teacher in Japan and then a crew member aboard Royal Caribbean cruise ships.

In Jim’s case, he worked as a media sales representative back in Iowa but was able to secure a position in the supply department in McMurdo.

The good news for those interested in going to the White Continent is that if you’re willing to do any job, even washing dishes or mopping the floors– you could get paid to live in Antarctica.

Learn more about living and working in Antarctica

Pre-Deployment to Antarctica: Applying and Waiting

The road to setting foot in Antarctica isn’t an easy one.

From the time Jim first began applying until he finally made it down to the ice, the entire process took about 14 months.

His journey began like many others— as an alternate.

Due to the complicated and lengthy series of medical examinations and screenings required to become physically qualified to work in Antarctica, the contractors for the Antarctic program always have a backup list of participants in case primary position holders are unable to deploy or complete their contracts.

The wait could be days, months, or even up to a year if no spots become available within the season.

Holding an alternate position could also mean very short notice between the initial primary position offer to the time you need to leave home.

After a successful phone interview in May of 2019, Jim spent the next 5-6 months getting his medical requirements completed.

Finally, in early December, he was given an on-ice contract to McMurdo and left Iowa five days later.

Working in McMurdo’s Supply Department

During Jim’s three-month stay in McMurdo, he held two positions in the supply department: first as part of the retrograde staff, and second as the auto shop supply room clerk.

A Typical Day on the Retrograde Team

Due to the international Antarctic Treaty, all waste must be shipped off the continent for disposal.

The role of the retrograde team is to prepare obsolete items for return to the U.S.

The day typically starts at 7:30 a.m. when team members arrive, stretch, and receive their assignments, which often varied.

For example, Jim recalls that one assignment was to move all stored items from a building that was to be torn down to a temporary storage location.

After everything was moved, they had to inventory the items.

Because the temporary storage was unheated, Jim and his coworkers would warm up in heated facilities every hour.

He also adds that during this assignment, his bathroom facility was a portable one— something that many McMurdans experience if their worksite isn’t one of the main buildings or if it’s in a more remote location.

At noon, the team breaks for a one hour lunch, then returns to work until 5:30 p.m.

A Typical Day as a Night Shift Supply Room Clerk

Jim’s second position was with the Vehicle Maintenance Facility (VMF) on the night shift, or as it’s known locally— the midrat shift.

The word “midrat” comes from “midnight rations,” which is the “lunch” meal at midnight reserved for the night shift workers.

During the height of the summer season, the station works around the clock offloading the entire next year’s supply of provisions and fuel that arrive via joint operations between the U.S. and New Zealand military.

Throughout this peak period, several departments’ schedules, including Jim’s, changes to 12-hour shifts in order to assist the offload crew.

In his role as the midrat VMF supply room clerk, Jim began work at 5:30 p.m.

Throughout the shift, he assists mechanics by retrieving parts they request.

After all the requests are caught up, Jim goes through the receiving items and puts them back in the proper locations.

When there are no items coming in, he’s in charge of performing needed inventory counts.

After a lunch break at midnight, Jim heads back to the VMF building to continue processing inventory or assisting the mechanics until the end of his shift at 7:30 a.m.

Related: Life at the South Pole Station: Everything You Want to Know

What a Medical Evacuation in Antarctica is Like

On March 12, 2020, only five days before his scheduled departure from Antarctica, Jim suffered a heart attack.

To understand just how lucky Jim was to have survived this ordeal on the ice, those unfamiliar with life in Antarctica might need some context.

McMurdo Station has a small medical facility, but it’s nothing close to the fully equipped hospitals you typically find in a city.

What might be a survivable health crisis at home can quickly turn into a life or death situation on the ice.

Besides the limited resources, arranging a medical evacuation at the end of the world is predictably as complicated as you’d expect.

It usually involves the organization of at least two, if not more, countries’ military and/or Antarctic programs.

In Jim’s case, a medevac request first went to New Zealand (the closest country to McMurdo), but they didn’t have any planes available.

The next option was to contact Australia, and they were the ones who eventually provided the evacuation staff and planes.

If both Australia and New Zealand weren’t able to assist, a plane would have been sent from the U.S.

And then there’s the weather.

Conditions can be unforgiving with very low visibility.

After February, it only gets worse as extreme cold and darkness sets in for the winter.

It’s not always possible to land a plane according to schedule and the delays can last days, not just hours.

According to ABC News, the conditions on the ice at the time of Jim’s rescue were -30 C (-22 F) with wind chill.

Fortunately, the medevac went smoothly and he was able to get off the ice just over 24 hours following his heart attack.

Jim’s private flight off the ice and to Christchurch included three pilots, two flight attendants, and three doctors.

He jokes that there were a hundred window seats available to him and yet he couldn’t look out any one of them as he understandably wasn’t allowed to move much throughout the flight.

After getting to the hospital in New Zealand, Jim was placed in an open ward in a room at the end of the hall in order to isolate him from other patients who could potentially have been infected with COVID.

The medical team knew Jim was COVID-free coming from Antarctica, and additional measures were taken around him to ensure that his exposure remained limited during his recovery.

Although he was released from the hospital after five days, he was under a no-fly order for two weeks.

New Zealand locked down just a few days after Jim arrived, so due to the reduced number of flights, he ended up staying in the country for a total of three weeks.

Thankfully, Jim had friends in Christchurch who hosted him after his hospital release.

On April 7, after three months in Antarctica and 26 days following his heart attack, Jim was finally able to fly home to Iowa.

Life After Working in Antarctica

While a harrowing experience might deter some– if not most– from returning to the ice, Jim is not one of these people.

Even up until the day he was evacuated, he wished he could’ve stayed longer.

Today, he’s currently in the process of returning for another season.

Frequently Asked Questions

I asked Jim to answer some common questions someone might have if they’re interested in working in Antarctica or applying for a position in the supply department.

1. What was the biggest challenge you faced on the ice?

Until the end, physical fitness.

2. What was the best part of your job?

Working with people that also wanted to be there.

3. What should first-timers know before applying or coming to the ice for your position?

If you know someone that has been there, talk to them about what to take. I took too much hygiene, but not enough correct layered clothing. Cotton works in Iowa, but not in Antarctica.

4. What would you pack next time that you didn’t originally?

Different undergarments (not cotton), and electronic books and magazines.

5. How did you spend your free time?

Writing, hiking, reading, going to the bars and library, touring the different facilities on station, talking to family on the phone, journaling, and writing articles for the paper back home.

6. What’s a fun fact about working on the ice that most people would be surprised to learn?

It’s not as cold as you think [during the summer]. On warm days, we can do physical work outside without coats.

7. What are your best memories from the ice?

Meeting life long friends (specifically my ice family 😉 ) and making it to the top of Observation Hill, an achievement that became more significant at the the end of my time on the ice.

8. Worst memory?

Waiting in medical for my flight home.

9. What did you miss most while on the ice?

Family.

10. What did you miss most after the ice?

The scenery, hikes, and new friends.

11. Do you have any regrets?

I wish I had done more hiking.

Want to learn more about life working and living in Antarctica? Check out these posts:

- How I Got Paid to Live in Antarctica: FAQ About Working on the Ice

- 20 Things You Didn’t Know About Life at McMurdo Station, Antarctica

- McMurdo Station Packing List for Working in Antarctica

- Life at the South Pole Station: Everything You Want to Know

- Working in Antarctica: Blaster Garry Rex | Stories From the Ice

- How to Get Paid to Travel to Every Continent (Yes, Even Antarctica)

Special thanks to Jim Huston for this interview.

If you’ve worked in Antarctica and have a story to share, I’d love to hear about it! Get in touch with me here.

Pin and Save

Leave a reply